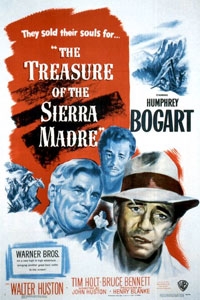

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) (NR) ★★★½

(Spoilers.)

(Spoilers.)

"The love of money is the root of all evil." So says the Bible. So also says B. Traven, the mysterious author whose novel The Treasure of the Sierra Madre became the source material for director John Huston's 1948 adaptation. A meditation about the effects of greed and isolation on the human psyche, this Oscar darling gave Humphrey Bogart his darkest role and Huston his greatest triumph with two award victories for himself (Adapted Screenplay and Director) and one for his father (Supporting Actor).

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre explores the personality disintegration of three men who, isolated from civilization during a prolonged prospecting excursion, are consumed by greed and paranoia. Part adventure story and part cautionary fable, the movie isn't afraid to venture into the dark places where the characters, especially Humphrey Bogart's Fred C. Dobbs, find themselves. The movie presents the accumulation of wealth not as a panacea to impoverished men but as a vice that debases them. The film ends on a note of bitter irony that underlies the ephemeral nature of fortune.

This was the second of four collaborations between director John Huston and Bogart. It came at a time when Huston's star was brightly ascending and Bogart was at his peak drawing power. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was sandwiched between two of the Bogart/Bacall films (1947's Dark Passage and 1948's Key Largo, also directed by Huston). When Bogart accepted the role, he was looking to broaden his range as an actor, having become stereotyped as the hard-edged but heroic persona he had played in the likes of The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, and The Big Sleep. Dobbs provided him with an opportunity to portray a villain - an ordinary man eaten up by avarice and mistrust that transform him into a thief and killer. (In describing Dobbs to a critic, Bogart said, "I play the worst shit you ever saw.") Audiences at the time loved Bogart but not this Bogart. One of the reasons The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was initially unsuccessful at the box office was because viewers didn't warm to the actor in this sort of a part, even though he considered it among his strongest performances (which it was).

Although The Treasure of the Sierra Madre provided Bogart with an chance to show that he could play more than a Sam Spade/Philip Marlowe-type, he was overshadowed by the director's father, Walter, who stepped into the role of an old-time prospector and font of wisdom, Howard. The best work of the elder Huston's illustrious career, which stretched back to 1929, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre earned him an Oscar for his turn as the fast-talking, level-headed leader of the group of drifters. The third member of the trio, Tim Holt, is often forgotten. His performance as Bob Curtin is solid but exists in the twin shadows of Bogart and Huston.

Filmed mostly on location in Mexico - a rarity for films of the era which were, more often than not, shot on backlots and sound stages in California - The Treasure of the Sierra Madre opens in 1924 Tampico where a labor contractor hires two unemployed American expatriates, Dobbs and Curtin, to work for him constructing oil rigs. When the jobs are done, he skips out without paying them, leaving the two men as desperate for money as they were beforehand. They meet an ex-prospector, Howard, and the three men pool their resources and head into the mountain looking for gold. What initially seems like a great adventure turns into a grueling slog. While Dobbs and Curtin become exhausted by the journey, the oldest member of the trio displays the energy of a billy goat. Led by Howard's impeccable instincts, they find a rich vein and spend months mining it. During the arduous process, Dobbs is nearly killed in a cave-in but his life is saved by Curtin - something he acknowledges at the time but later forgets as his sanity erodes. Paranoia assails the men, as is illustrated in a night scene when each fears the others might be looking for their hidden shares of the riches.

The three men aren't alone in the wilds. A Texas wanderer, Cody (Bruce Bennett), comes upon them and presents them with a choice: they can allow him to join them or they can kill him. Rather than splitting their future earnings into four parts and fearful of the newcomer's motives, Howard, Dobbs, and Curtin decide on the latter option. Before they can make good on the threat, however, they are attacked by bandits. The timely arrival of Federales chases away the thieves but Cody dies in the skirmish. Increasingly fearful for their safety and believing the vein to be running dry, the three prospectors decide to go home. Along the way, Howard leaves the group to help a local native boy and, after his departure, Dobbs attacks Curtin, shooting him and leaving him for dead. This sets in motion a chain of events that results in Dobbs' death at the hands of the bandits and the loss of all the gold. Howard chooses to stay with the Indians and Curtin, once recovered, heads to Texas to locate Cody's widow.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is the source of one of movie-dom's most famous misquotations. The line normally attributed to the bandit Gold Hat (Alfonso Bedoya) is "We don't need no stinkin' badges!" What he actually says is "Badges? We ain't got no badges. We don't need no badges! I don't have to show you any stinkin' badges!" As with "Play it again, Sam," there's a tendency to mis-remember famous passages from Bogart classics.

The movie stands up well today, with its themes as relevant in the 2010s as they were in the 1940s. Times change and technology advances but the essence of humanity remains immutable and, more than anything, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is about the dark side of human nature. Arguably the best film directed by Huston and among the most impressive screen turns by Bogart, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre has been cited as a favorite film by the likes of Stanley Kubrick, Sam Raimi, and Paul Thomas Anderson. It has been re-imagined (particularly by Sam Peckinpah and Robert Altman) but never surpassed. Watching the movie reminds us that, even amidst the post-World War II optimism (when a great cloud had been lifted), there was an understanding that base forces like greed and selfishness can lead to madness and, in that madness, lurks a bleak and impenetrable darkness.

© 2019 James Berardinelli

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Civil War Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura 11.1M

Abigail Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Melissa Barrera, Dan Stevens 10.2M

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 9.5M

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Henry Cavill, Eiza Gonzalez 9M

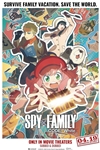

Spy x Family Code: White Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Takuya Eguchi, Saori Hayami 4.9M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Viola Davis 4.6M

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon 4.4M

Dune: Part Two Released: March 1, 2024 Cast: Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson 2.9M

Monkey Man Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Dev Patel, Sikandar Kher 2.2M

The First Omen Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Nell Tiger Free, Bill Nighy 1.7M