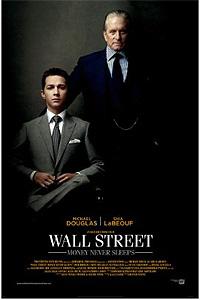

Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (PG-13) ★★★

Much has changed in the world of finance since Oliver Stone first explored its grubby innards in 1987's Wall Street, a film that netted Michael Douglas a Best Actor Oscar for his iconic portrayal of scheming corporate raider Gordon Gekko. Technological advances, regulatory changes, a terrorist attack, a global economic meltdown, and the emergence of China as a dominant player have combined to transform the securities industry in the two-plus decades since Gekko, paraphrasing Ivan Boesky, first captured its more sinister aspects in those famous words, "Greed is good."

Much has changed in the world of finance since Oliver Stone first explored its grubby innards in 1987's Wall Street, a film that netted Michael Douglas a Best Actor Oscar for his iconic portrayal of scheming corporate raider Gordon Gekko. Technological advances, regulatory changes, a terrorist attack, a global economic meltdown, and the emergence of China as a dominant player have combined to transform the securities industry in the two-plus decades since Gekko, paraphrasing Ivan Boesky, first captured its more sinister aspects in those famous words, "Greed is good."

What hasn't changed is Stone, who remains every bit as hubristic and heavy-handed as ever. With his sprawling, spotty follow-up, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, he has once again taken it upon himself to put forth the definitive portrait of the culture of money, and the film suffers badly for it. Set in 2008, in those halcyon days just prior to the subprime mortgage crisis and its subsequent leveling of financial landscape, the film is told through the wide eyes of young Jake Moore (Shia LaBeouf), the 21st-century heir to Bud Fox's mantle. (Charlie Sheen, who portrayed Fox in the first film, resurfaces in a fun but ultimately pointless cameo in the sequel.)

Jake, we are told, is a successful proprietary trader, but his countenance more closely resembles that of a venture capitalist. (The risky practices and alleged conflicts of interests of prop traders are widely believed to be among the causes of the financial collapse; the Obama administration has recently proposed their ban.) Though he's as profit-driven as any other young Wall Street turk, he also boasts something of an idealistic streak, and hopes to use his position at the prestigious investment banking firm of Keller Zabel to further the cause of a cutting-edge green energy startup. No doubt it's this noble trait that appeals to his girlfriend Winnie (Carey Mulligan), a progressive pixie who runs a muckraking leftist blog, and who also happens to be Gekko's estranged daughter.

Jake's bright future takes a dark turn when rumors of over-exposure to "toxic assets" swallow up first his company, Keller Zabel, and then its founder, Lou (Frank Langella), who opts to retire beneath a speeding subway train after the Federal Reserve denies his request for an emergency bailout. Devastated by the suicide of his boss and mentor, Jake vows to exact revenge upon the slithery brute he believes to be the source of the poisonous rumors: Bretton James (Josh Brolin), a prominent partner at Churchill Schwartz (read: Goldman Sachs), Keller's chief rival.

And where, exactly, does Gordon Gekko figure in all of this? After the opening sequence, during which he emerges from a lengthy prison stay to find no one waiting to greet him, Gekko doesn't re-enter the story until about the 30th minute, and lurks mainly on its periphery for much of his screen time. In the years since his incarceration for the various misdeeds chronicled in the first film, he's rebranded himself as a sort of populist crusader against speculator avarice, hawking a book about the ills of the financial system entitled Is Greed Good? ("You're all pretty much fucked," he instructs a lecture audience.) Gekko's got a grudge of his own against Bretton, his one-time protege turned state's witness in his securities fraud conviction, and he agrees to supply Jake with crucial insider info in exchange for help in brokering a reconciliation with his daughter Winnie.

All of this is set against a backdrop of the collapses and bailouts of the 2008 financial tumult — a topic that could easily warrant its own film. (Indeed, HBO is currently readying its adaptation of Aaron Ross Sorkin's book about the crisis.) His ambition outstripping his ability, Stone labors awkwardly to integrate the macro of the crisis, with its many backroom deals and soap-opera intrigues, and the micro of Jake's increasingly complex relationship with Gekko. Mulligan's character, meant to serve as the film's emotional anchor as well as its conscience, is ultimately little more than a distraction, diverting us from the story's more compelling elements. The last third of the film, which focuses on Gekko's reemergence as a Wall Street player, feels tacked-on, as if driven by data from test audiences dissatisfied with his relatively minor presence in the early goings.

There are moments in Money Never Sleeps where Stone successfully invokes the heady verve of the 1987 film, but for a story dealing with such titillating subject matter, its pace too often drags to a near-halt as it wallows excessively in Gekko family melodrama. (The performances, it should be noted, are all terrific, though LaBeouf is an exceedingly tough sell as a would-be BSD.) And a topic as sexy as money should never, ever be boring.

Hollywood.com rated this film 3 stars.

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Civil War Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura 11.1M

Abigail Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Melissa Barrera, Dan Stevens 10.2M

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 9.5M

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Henry Cavill, Eiza Gonzalez 9M

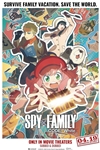

Spy x Family Code: White Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Takuya Eguchi, Saori Hayami 4.9M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Viola Davis 4.6M

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon 4.4M

Dune: Part Two Released: March 1, 2024 Cast: Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson 2.9M

Monkey Man Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Dev Patel, Sikandar Kher 2.2M

The First Omen Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Nell Tiger Free, Bill Nighy 1.7M