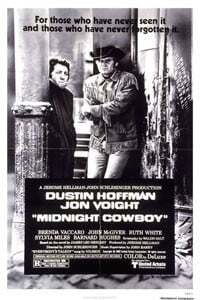

Midnight Cowboy (R) ★★★

(Spoilers, as one might expect from a retrospective of a 50-year old movie.)

(Spoilers, as one might expect from a retrospective of a 50-year old movie.)

Midnight Cowboy, the only X-rated film to win a Best Picture Oscar, is less shocking than its reputation might indicate. Essentially a two-character buddy film, the majority of the story focuses on the relationship between Texas-born self-styled "cowboy" Joe Buck (Jon Voight) and homeless street con-man Rico "Ratso" Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman). Like all buddy films, this one relies heavily on the lead performances and the actors' chemistry. It also descends into darker territory than what one often finds in movies of this sort.

Although Midnight Cowboy contains moments of levity, it grows increasingly darker. What begins as an acquaintanceship of convenience develops into a co-dependent relationship that even the most liberal-minded individual would deem to be unhealthy. Joe is an innocent fish-out-of-water in New York City, and Ratso knows how to exploit him. He does so relentlessly, even when his physical infirmity demands that he rely on the younger, healthier man. Only in a fantasy sequence, which depicts Joe and Rizzo living the good life in Miami, do we ascertain that the affection between the two is mutual.

Director John Schlesinger elects to open Midnight Cowboy with a light, nostalgic montage. Set to the strains of Harry Nilsson's "Everybody's Talkin'," it depicts Joe's final moments in Texas as he resigns his job as a dishwasher and boards a bus heading to Manhattan. His goal is to get rich by becoming a prostitute and selling his body to old, rich women and wealthy gay men. He comes to realize two things: (1) it's harder than he thinks and (2) he's not good at it. His first "job" goes so badly and he ends up paying his customer when it's over. (This is one of the film's openly comedic sequences.) His second job ends with no money changing hands because his "client" doesn't have anything with which to pay. Enter Rizzo, who claims to know what Joe's problem is: he needs a pimp.

For a fee, Rizzo agrees to hook up Joe with one, the notorious Mr. O'Daniel (John McGiver). Turns out that, although O'Daniel may at one time have been involved in the sex trade, he's now a religious fanatic set on converting all who cross his path. An angry Joe, soon penniless and evicted from his hotel, tracks down Rizzo, who shows hints of contrition. (Real? Contrived? We're not sure.) He invites the Texan to move into his squat so they can plan their next move. Their get-rich-quick scheme doesn't work well and, as Rizzo's cough becomes acute (hinting at a serious illness), Joe takes on a caregiver's role. Following his first success as a hustler, a $20 session with an upscale woman named Shirley (Brenda Vaccaro), Joe returns to the squat to find Rizzo failing. They board a bus to Miami but Rizzo doesn't survive the trip.

Midnight Cowboy established Jon Voight as a performer to be reckoned with. Prior to the film, he had a thin resume. After it, he had critical raves and an Oscar nomination. Less than a decade later, he would take home the coveted Best Actor statue for his work in Coming Home. Voight, a native New Yorker, wasn't Schlesinger's first choice to play Joe (that was Lee Majors, but the future Six Million Dollar Man was locked into a contract for the TV show The Big Valley), but his contribution to the film proved to be invaluable. He was not only able to master the Texas accent but portray the optimism and naïveté of the character. Joe never gives into the cynicism that has mastered Rizzo and the only time he becomes violent is when desperation forces his hand. Voight's desire to play Joe was so strong that he accepted "scale" pay (the SAG minimum wage) to do so.

Unlike his co-star, who was relatively unknown at the time, Dustin Hoffman was an established figure (chiefly as a result of The Graduate), but not for the type of role he would play in Midnight Cowboy. At the time, there was some concern that his against-type playing of Rizzo would damage his career. The result was the opposite: Midnight Cowboy demonstrated Hoffman's range - how there was more to him than a good-hearted young man. His portrayal of Rizzo was not only convincing but deeply affecting. Voight has more screen time yet Hoffman leaves a more forceful impression. His ad-libbed line of "I'm walking here!" became iconic. Like Voight, he was nominated for an Oscar (they both lost to John Wayne for True Grit). He would win his first Best Actor award (for Kramer vs. Kramer) the year after Voight won his.

Midnight Cowboy's history with the MPAA is indicative of changing cultural norms. The film's frank (although not pornographic) depiction of homosexual activity crossed taboo lines in the late 1960s. (There is also a subtle undercurrent of homoeroticism in the Joe/Rizzo relationship, although this remains unacknowledged by the characters.) The initial X rating was not questioned by either Schlesinger or United Artists. (John Wayne had an opinion. In a contemporaneous Playboy interview, he said the following: "Wouldn't you say that the wonderful love of these two men in Midnight Cowboy, a story about two fags, qualifies as...perverse...?") Shortly thereafter, porn movies began co-opting "XXX" as a marketing ploy; the indirect result was to tarnish "legitimate" X-rated films like Midnight Cowboy. Reacting to this, the MPAA tweaked the R rating to raise the age barrier from 16 to 17 ("Under 17 not admitted without parent or guardian.") Without making any content changes, Midnight Cowboy was re-rated with an R. Today, although the film's content is on par with other R-rated films, it's closer to PG-13 than NC-17. Scenes that were shocking to audiences in 1969 would scarcely result in a raised eyebrow today.

To the extent that an element of Midnight Cowboy's success was related to its unflinching approach to daring material, the shifts in society's views have diminished that aspect of the production. What have survived, however, are the complexity of the relationship between the two main characters and the tragic arc inscribed by their interaction.

© 2019 James Berardinelli

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Civil War Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura 11.1M

Abigail Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Melissa Barrera, Dan Stevens 10.2M

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 9.5M

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Henry Cavill, Eiza Gonzalez 9M

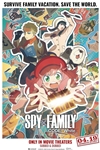

Spy x Family Code: White Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Takuya Eguchi, Saori Hayami 4.9M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Viola Davis 4.6M

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon 4.4M

Dune: Part Two Released: March 1, 2024 Cast: Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson 2.9M

Monkey Man Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Dev Patel, Sikandar Kher 2.2M

The First Omen Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Nell Tiger Free, Bill Nighy 1.7M