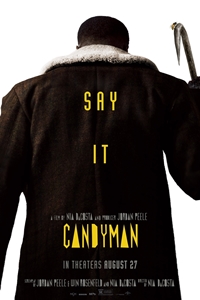

Candyman (R) ★★★

At the time of its October 1992 release, I wrote the following about the original Candyman (which was directed by Bernard Rose based on a story by Clive Barker): "Candyman is one of the most intelligent and chilling movies to grace the screen in a long while. There's no shortage of blood and gore, but human insides splattered all over aren't the focus. Candyman isn't a slasher movie. It makes use of the most powerful of human motivators: the imagination. Created with the thinking movie-goer in mind, Candyman may be the Halloween of the nineties." That's a lot for a sequel/reboot to live up to. Fortunately, due in large part to the unconventional approach chosen by director Nia DaCosta and screenwriters Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld, the new Candyman proves to be a worthy follow-up to its namesake.

At the time of its October 1992 release, I wrote the following about the original Candyman (which was directed by Bernard Rose based on a story by Clive Barker): "Candyman is one of the most intelligent and chilling movies to grace the screen in a long while. There's no shortage of blood and gore, but human insides splattered all over aren't the focus. Candyman isn't a slasher movie. It makes use of the most powerful of human motivators: the imagination. Created with the thinking movie-goer in mind, Candyman may be the Halloween of the nineties." That's a lot for a sequel/reboot to live up to. Fortunately, due in large part to the unconventional approach chosen by director Nia DaCosta and screenwriters Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld, the new Candyman proves to be a worthy follow-up to its namesake.

Like David Gordon Green's Halloween, DaCosta's Candyman ignores all the sequels and posits itself as a direct follow-up to the original. And, like the most recent Halloween, this Candyman works because it doesn't rely exclusively on nostalgia and slasher elements (although both are present); instead, it explores new avenues and, although there are times when the screenplay wanders into cul-de-sacs (one of which occurs in a high school girls' bathroom), it achieves the aim of being faithful to its predecessor while introducing new themes and ideas.

Because a certain (albeit minimal) familiarity with the 1992 film is necessary to understand the backstory, Candyman helps viewers by using animated sequences that recreate (via shadow puppets) the necessary moments. These Tim Burtonesque scenes allow DaCosta to bypass either (a) using lengthy excerpts from the earlier film, (b) remaking scenes, or (c) having lengthy stretches of expository dialogue. One of the film's conceits is that Candyman is a non-corporeal entity that appropriates bodies. Although this idea wasn't in either Rose's screenplay or Barker's source material, DaCosta ensures that it fits seamlessly into the overall narrative. It also allows Tony Todd to participate in a meaningful fashion.

Candyman opens with a flashback to events in 1977 that transpire in the infamous housing projects of Chicago's Cabrini Green. It's there that a boy has his first, life-changing encounter with a man with a hook for an arm and a penchant for giving out sweets. Flash-forward to the present day. Artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), seeking inspiration, decides to explore the history of the gentrified Cabrini neighborhood into which he has recently moved with his girlfriend, Brianna Cartwright (Toyonah Parris). His investigations inevitably unearth the decades-old story of the Candyman, a supernatural figure who manifested with a murderous intent whenever anyone looked into a mirror and said his name five times. After speaking to a long-time resident of the projects, William Burke (Colman Domingo), Anthony develops an obsession with Candyman. His paintings become lurid and macabre and his body begins to manifest physical signs of disease and decay. Eventually, he seeks out his mother, Anne-Marie (Vanessa Williams), who tells him a truth she had hoped to hide from him.

Those expecting a slasher-movie gore-fest will be disappointed by at least the film's first hour (the body count jumps dramatically during the final third). In fact, Candyman is less a physical presence and more an idea for much of the running time. Past and present eventually dovetail and Candyman arrives in the flesh but for more than half of the movie, the story focuses on Anthony's downward spiral. This provides the filmmakers with an opportunity to emphasize the themes of gentrification and how persistent police brutality can give birth to horrifying consequences. Candyman has always been a vengeful spirit; here, its apparitions are directly tied to racist torture and murder.

Although Candyman has been devised as a direct sequel to the first film with the thirty-year time differential baked into the narrative, the style and feel are different from those employed by Rose. DaCosta opts for less of a traditional "horror" approach, eschewing jump-scares in favor of a moody darkness. There is one overt homage to the slasher genre that gave birth to Candyman but it seems so tonally different (and unnecessary) that it feels grafted-on rather than organic. The ending allows for the possibility of another installment but doesn't demand it. If there's never another Candyman, this can function as a satisfying coda.

The movie belongs to Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, whose highest-profile to-date was in James Wan's Aquaman. His portrayal of the obsessed, psychologically imploding Anthony represents the film's foundation. Whereas the other Candyman movies were primarily about the title character, that's not the case here. Todd's efforts are consequential but he is kept in the background to allow Abdul-Mateen to remain in the spotlight. In addition to Todd, Vanessa Williams is also back from the original Candyman. Virginia Madsen provides vocal cues, although it's not clear whether these are new recordings or excerpts from the first film.

Candyman fits within the milieu of producer/co-writer Jordan Peele. Like Get Out and Us, it uses the genre as a means to explore social and cultural issues associated with race relations and racism. The "Candyman" of Clive Barker's envisioning has become something more ominous and substantial than the boogeyman found in the pages of "The Forbidden." This is one instance in which the return of a horror icon has a greater purpose than the exploitation of a recognizable brand. Would that more genre films were as thoughtful and thought-provoking, mixing substance with splatter in a fashion that builds uneasiness on more than one level.

© 2021 James Berardinelli

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Civil War Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura 25.7M

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 15.5M

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon 5.8M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Viola Davis 5.5M

Dune: Part Two Released: March 1, 2024 Cast: Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson 4.3M

Monkey Man Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Dev Patel, Sikandar Kher 4.1M

The First Omen Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Nell Tiger Free, Bill Nighy 3.8M

The Long Game Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Dennis Quaid, Gillian Vigman 1.4M

Shrek 2 Released: May 19, 2004 Cast: Mike Myers, Eddie Murphy 1.4M

Sting Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Alyla Browne, Ryan Corr 1.2M