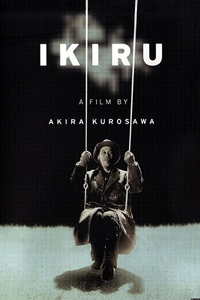

Ikiru (To Live) (NR) ★★★★

Those who know Akira Kurosawa only for his samurai movies (a genre that includes his most famous titles) may be surprised when exposed to the "other side" of his work - less ostentatious films like Red Beard, High and Low, and (most notably) Ikiru. A thoughtful, existential meditation about the meaning of life and what constitutes a life well-lived, Ikiru is almost guaranteed to prod the viewer to examine his or her own mortality and ponder how, in the end, the scales will tip.

Those who know Akira Kurosawa only for his samurai movies (a genre that includes his most famous titles) may be surprised when exposed to the "other side" of his work - less ostentatious films like Red Beard, High and Low, and (most notably) Ikiru. A thoughtful, existential meditation about the meaning of life and what constitutes a life well-lived, Ikiru is almost guaranteed to prod the viewer to examine his or her own mortality and ponder how, in the end, the scales will tip.

Ikiru was made in 1952 - in between 1950's Rashomon and 1954's Seven Samurai. Although Kurosawa's relationship with frequent lead actor Toshiro Mifune was already cemented by the time Ikiru came into being, Kurosawa opted not to use Mifune in this instance (it's the only film Kurosawa made between 1948 and 1965 that didn't feature Mifune), instead entrusting the lead role of Kanji Watanabe to Takashi Shimura who, at fifteen years Mifune's senior, was able to craft an older, more jaded personality. Overall, Shimura was second only to Mifune in finding favor with Kurosawa, having appeared in 21 of the director's 30 features (although often in secondary roles, supporting Mifune's lead). He is unquestionably best remembered for his part in Ikiru. (Although some kaiju fans might argue in favor of Godzilla.)

Central to Ikiru's DNA is the concept of carpe diem (the title can be literally translated as To Live). But this is no Dead Poets Society. Kurosawa approaches the idea with a combination of reverence and melancholy. He also uses it as an opportunity to skewer the intransigence of the bureaucratic mentality. The director also eschews a traditional, chronological approach. Although the film's first two-thirds are linear, the final 40 minutes use flashbacks from various characters to present a mosaic of the protagonist's actions during the final few weeks of his life.

When we first meet Kanji, he is immersed in his role in Tokyo's City Hall: a cog in a relentless machine. He sits at his desk, surrounded by piles of papers, in a scene that Terry Gilliam may have re-imagined in Brazil. Later, another character describes it thus: "We have to act like we're doing something while doing nothing." Kanji, reflecting back on his time in job, notes: "All these 30 years, what have I been doing there? I can't remember no matter how I try. All I remember is just being busy, and even then I was bored." Each day is like the one before - an unending litany of pointlessness. A female colleague admits the following to Kanji after he has taken an unprecedented vacation: "I'm bored. It's killing me. Every day is like the one before. Nothing new ever happens. I've put up with it for a year and a half, but the only novel thing that's happened was that you took five days off."

The shock to the system comes when Kanji learns that his stomach pains are caused by terminal cancer. Faced with a meaningless life, he opts not to continue with the daily grind. He briefly samples hedonism, allowing himself to be mentored by the Novelist (Yunosuke Ito). After meeting Kanji at a late-night drinking establishment, the Novelist offers, "Tonight it will be my pleasure to act as your Mephistopheles, but a beneficent one who won't ask for your soul." He diagnoses Kanji's condition: "Misfortune teaches us the truth. Your cancer has opened your eyes to your own life. People are fickle and shallow. We only realize how beautiful life is when we face death. And even then, few of us realize it. The worst among us know nothing of life until they die." Yet, despite the Novelist's best efforts to open Kanji's eyes to the pleasures around him, he remains unmoved.

During Ikiru's final act, which occurs at his wake, we learn how he spent the latter months and days of his life: bulldozing through red tape to enable a playground to be built for the neighborhood children. It's a small endeavor but it gives meaning to his time on Earth and allows him to be venerated by the fellow bureaucrats who piously claim they will now live their lives following his example. The lie of that utterance is given form in one of the film's closing scenes.

By constructing the film's third act in the manner that he does, Kurosawa is able to balance the peace Kanji finds with the realization that it will change nothing (except for those children who use the park). His actions don't provoke a revolution. The drunken attendees at his remembrance ceremony experience a brief awakening but, when it comes time to return to work (where "we're not expected to do anything"), it's gone. Ikiru doesn't opt for a Pollyanna-ish conclusion but it is satisfying on an intimate level. Kanji is provided with an opportunity to wake up and do something. He doesn't die unloved and forgotten. He finds a way to leave an impression.

The most moving moments of Ikiru occur during two scenes when "Song of the Gondola" is being sung. It's a sad, haunting ballad from 1915 that encapsulates the movie's themes (especially the verse: "life is brief; fall in love, maidens, before the raven tresses begin to fade; before the flame in your hearts flicker and die; for today, once passed, is never to come again"). On the first occasion, Kurosawa holds the camera in a closeup of actor Takashi Shimura's face as he absorbs each word. In the second instance, Kanji sits on a swing in a snowstorm awaiting his death. The scene is both eerie and serene.

Some have argued that Ikiru is Kurosawa's most accomplished film and, based on some of the director's own quotes, he may have agreed. It's certainly different from any of his other well-known movies and delivers an emotional punch without the manipulation one often expects from movies that address a similar subject matter. Although by no means "unknown," Ikiru deserves to be recognized on an equal footing with Kurosawa's other masterpieces.

© 2021 James Berardinelli

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Challengers Released: April 26, 2024 Cast: Zendaya, Josh O'Connor 15M

Unsung Hero Released: April 26, 2024 Cast: Daisy Betts, Joel Smallbone 7.8M

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 7.2M

Civil War Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura 7M

Abigail Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Melissa Barrera, Dan Stevens 5.3M

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Henry Cavill, Eiza Gonzalez 3.9M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Viola Davis 3.6M

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon 3.3M

Dune: Part Two Released: March 1, 2024 Cast: Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson 2M

Boy Kills World Released: April 26, 2024 Cast: Bill Skarsgård, Famke Janssen 1.7M