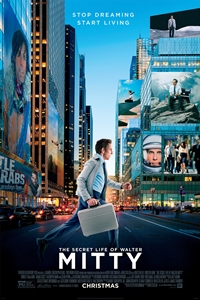

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013) (PG) ★★★★½

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty has to stand as the most endearing film of Ben Stiller's directing career. Working with screenwriter Steve Conrad (no stranger to sentimentality as the man behind The Pursuit of Happyness and The Weather Man), Stiller has produced a film rejoicing YOLO culture that eschews the hashtag. Based on a short story by James Thurber that also became a 1947 film with Danny Kaye, the material is updated to feel more in line with this era, considering the notion of human interaction perverted by the filter of technology.

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty has to stand as the most endearing film of Ben Stiller's directing career. Working with screenwriter Steve Conrad (no stranger to sentimentality as the man behind The Pursuit of Happyness and The Weather Man), Stiller has produced a film rejoicing YOLO culture that eschews the hashtag. Based on a short story by James Thurber that also became a 1947 film with Danny Kaye, the material is updated to feel more in line with this era, considering the notion of human interaction perverted by the filter of technology.

The titular character, played by a restrained Stiller, works at Life magazine as a “negative asset manager.” In other words, he manages the magazine's library of film negatives in a dark room, behind the scenes. He seems content to skate through life finding thrills in daydreams while avoiding anything risky. His lapses into fantasy are depicted twofold: On the one side they are stagey, hyper-choreographed sequences heavily reliant on digital effects. On the other, they are moments where Walter seems to freeze and “zone out.”

The delusions reach heights of fancy that harness Stiller's humor at its most whimsical. There's one fight sequence that could fit right in with anything in Scott Pilgrim vs. The World. Sometimes these sequences are cloyingly contrived as they reach and reach for easy laughs. The humor of these over-the-top fantasies is so exaggerated that it often undermines the tone of the film… except maybe in the case of one brilliant sequence where Walter imagines himself coming down with “Benjamin Button's Disease,” so he might garner pity from the woman of his dreams, co-worker Cheryl Melhoff (Kristen Wiig, tempering her shtick down to levels of cool sweetness).

Thankfully, the contrivance does not saturate the movie, as Stiller has created a work that looks to the more subtle layers of fantasy that permeate popular culture. Stiller steers the film beyond Walter's own obvious entanglements and takes subtle jabs at other characters as well. Walter doesn't have the monopoly on a warped sense of self-perception. His nemesis, Ted Hendricks (Adam Scott), has arrived at Life as a “fixer” to shift the magazine into the digital age. He's cocky and self-assured. He knows that the Internet, that vast of ocean of nothing turned into something by pixels and algorithms, is Life magazine's future. His delusions take hilarious physical form in a beard that makes him look like a gawky Hans Gruber, which he wears like some vain hipster jumping on a trend.

It's a hint that there is more to this film than contrived fantasy sequences designed for undemanding laughs. The film buries Walter's clunky daydreams for something much more grounded after a frame, which is supposed to be the cover of Life's last issue and captures “the quintessence of life,” goes missing. After Ted orders him to not show up to work without that frame, Walter decides to go looking for the man who shot the image, the magazine's star photographer Sean O'Connell (Sean Penn), following a trail of clues to Iceland and Afghanistan. To reveal whether Walter finds Sean is immaterial; the big question is whether Walter can find himself.

Behind the cute notion of a man so detached from reality he finds comfort in the world of daydreams lies a grander message. For all its notions of escapism, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty winds its way to a rather grounded sentiment that celebrates connection with the real, unadulterated moment without filters, be they through fantasy or technology. It's about the pleasures of experiences over daydreams, analog over digital, effort over ease, enjoying the doing and not the done, and patience over immediate satisfaction. So much of the essence of these notions is folded into the dynamics of the film's characters and their interactions, in the writing and the set pieces. Stiller harnesses the power of cinema to show what it can do, then subverts it. On a meta level, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty doesn't draw you into the cinema, as much as tell you to get out of it.

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Civil War Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura 11.1M

Abigail Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Melissa Barrera, Dan Stevens 10.2M

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 9.5M

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Henry Cavill, Eiza Gonzalez 9M

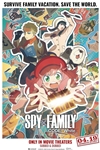

Spy x Family Code: White Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Takuya Eguchi, Saori Hayami 4.9M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Viola Davis 4.6M

Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire Released: March 22, 2024 Cast: Paul Rudd, Carrie Coon 4.4M

Dune: Part Two Released: March 1, 2024 Cast: Timothée Chalamet, Rebecca Ferguson 2.9M

Monkey Man Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Dev Patel, Sikandar Kher 2.2M

The First Omen Released: April 5, 2024 Cast: Nell Tiger Free, Bill Nighy 1.7M