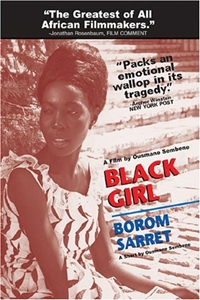

Black Girl (La noire de...) (NR) ★★½

Black Girl is the feature debut of acclaimed African author-turned-filmmaker Ousmane Sembene. Clocking in at roughly an hour in length, the movie suffers from a number of what might be considered "teething" flaws: uneven pacing, wooden acting, underdeveloped characters, and a lack of elegance in advancing its political themes. Nevertheless, despite these various issues, Black Girl remains an important milestone in 20th century motion pictures. Not only was it the "first sub-Saharan African film to achieve international attention," but it marked the launch of the career of a man who became an important force in African cinema. Sembene made better films than Black Girl (his final feature, the searing Moolade, is one of his most powerful) but the roots of his oeuvre can be seen here.

Black Girl is the feature debut of acclaimed African author-turned-filmmaker Ousmane Sembene. Clocking in at roughly an hour in length, the movie suffers from a number of what might be considered "teething" flaws: uneven pacing, wooden acting, underdeveloped characters, and a lack of elegance in advancing its political themes. Nevertheless, despite these various issues, Black Girl remains an important milestone in 20th century motion pictures. Not only was it the "first sub-Saharan African film to achieve international attention," but it marked the launch of the career of a man who became an important force in African cinema. Sembene made better films than Black Girl (his final feature, the searing Moolade, is one of his most powerful) but the roots of his oeuvre can be seen here.

Black Girl has a minimalist plot. The main character, Diouana (Mbissine Therese Diop), is a young black woman hired off the streets of Dakar by a wealthy white Frenchwoman (Anne-Marie Jelinck). She and her husband (Robert Fontaine) live there part-time and Diouana is engaged to look after their children. She loves the job and is enamored with the family. When given the opportunity to move with them back to France, she eagerly accepts. Once there, however, she discovers that things have changed. The convivial couple have become cold and harsh. Diouana is expected to do menial chores never required of her in Dakar - cooking, cleaning, and washing. She never leaves the house and gradually becomes overcome by a creeping moroseness and self-pity. Her final solution shocks the husband but seems more like a source of inconvenience for the self-absorbed, entitled wife.

The movie's "present" is in France but Sembene fills in the details through a series of flashbacks that illustrate Diouana's difficulties with her boyfriend and ailing mother prior to her engagement by the French couple. In a device that betrays Sembene's literary background (he was a writer prior to making movies), he elects to have his lead actress remain mute throughout the film, instead providing access to her thoughts via a voiceover narrative/internal monologue. The result is an oddly disconnected character.

Sembene is less interested in the interplay among the characters or, indeed, in the characters themselves, than he is in using them to represent aspects of themes he frequently returned to in his writing and films: colonialism, racism, and post-colonial identity in Africa and France. The attitudes of the white characters toward the black ones reflect a superiority that, although evident in Dakar, is amplified in France. The wife's mindset is that of a slave-owner who expects unquestioned subservience - she threatens to withhold food if Diouana won't work. This dynamic and how it plays out is more important to Sembene than dissecting the characters. They are pawns in a morality play.

That's not to say the circumstances aren't of interest. They are tragic because they mirror real-world concerns that resulted from how France divested itself of its colonies and the unhealed wounds left behind by the divorce. White French citizens living in Dakar exude preeminence over the indigenous population - a view often shared by the black men and women who clamor for work and recognition. Although America has its own sad history of civil injustice, watching Black Girl serves as a reminder that, if there's a high ground to be claimed, France doesn't have it.

The film's unpolished style results in some scenes that go on for too long, edits that are at times clumsy, and uneven performances given the mostly non-professional cast. Lead actress Mbissine Therese Diop (making her feature debut) strikes an imposing figure and uses her expressive features to provide insight into her character's thoughts. The voiceover monologue is at times at odds with Diop's performance, telling us what Diouana thinks rather than allowing us to decide based on the actress' physicality. Professional actors Anne-Marie Jelinck and Robert Fontaine play types - not legitimate characters but people as seen through Diouana's increasingly angry and disillusioned perspective. The skewed point-of-view, however, calls into question some of the points Sembene is making about the relationships between whites and blacks in this dynamic because we're never sure how much of the friction is "real" and how much derives from the use of an unreliable narrator's point-of-view.

As is often the case with international films of this period, the greatest value in Black Girl may be using it as a prism to understand things about the world at the time the movie was made. Whatever its faults, Black Girl takes us into the heart of a world that may be strange and unfamiliar to those who watch it today. This is no Hollywood-produced, glamorized perspective of a Dakar from 50 years ago - it's a sincere, urgent look at issues that have since metastasized to create problems that plague contemporary Europe. The short running time invites the interest of those more fascinated by the social climate and its associated message than the thin story and half-developed characters. For those who wish to investigate Sembane's filmography in detail, there's arguably no better place to start than at the beginning, especially when one understands that deeper, more compelling productions were to come.

© 2018 James Berardinelli

To get the full Quicklook Films experience, uncheck "Enable on this Site" from Adblock Plus

box office top 10

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes Released: May 10, 2024 Cast: Owen Teague, Freya Allan 56.5M

The Fall Guy Released: May 3, 2024 Cast: Ryan Gosling, Emily Blunt 13.7M

Challengers Released: April 26, 2024 Cast: Zendaya, Josh O'Connor 4.7M

Tarot Released: May 3, 2024 Cast: Harriet Slater, Adain Bradley 3.5M

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire Released: March 29, 2024 Cast: Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry 2.5M

Unsung Hero Released: April 26, 2024 Cast: Daisy Betts, Joel Smallbone 2.3M

Kung Fu Panda 4 Released: March 8, 2024 Cast: Jack Black, Awkwafina 2M

Civil War Released: April 12, 2024 Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Wagner Moura 1.8M

Star Wars Episode 1 The Phantom Menace 25th Anniversary Released: May 3, 2024 Cast: Ewan McGregor, Liam Neeson 1.5M

Abigail Released: April 19, 2024 Cast: Melissa Barrera, Dan Stevens 1.1M